The Battle of Hastings

The fight for Senlac Ridge on October 14th 1066 is probably the only battle date that most Englishmen can be expected to remember. Nearly a thousand years after the event, the memory of the resounding defeat of the last native Saxon King and his army rings down the centuries. But why did the battle take place? Why did William the Bastard, Duke of Normandy, think that he had a claim to the English throne in the first place. Or was it just an adventure; an enormous gamble that paid off and changed the course of world history in the course of an autumn day?

To try to see the events of those times in perspective across a such a vast stretch of time is difficult indeed. Most of the contemporary reporters were writing for a Norman audience and sought to support what even William saw in later life as an unjust cause. These notes have no scope to do anything but outline the causes and expectations of the principal protagonists, but a short reading list is attached for those who would like to follow them up.

Claimants to the English throne

King Harold II of England

In order to see Harold clearly, it is necessary to look at his family background in relation to the state. His father, Godwin, became an important man when Cnut came to the English throne. Nothing is known of his history until then, but he rose swiftly to become the most powerful Earl in the Kingdom. His genius lay in the gaining and exercise of power and by the age of thirty, he acted as effective ruler of England when the King was overseas. He survived the death of Cnut and the short, turbulent reigns of his sons Harold and Harthacnut with his lands and influence undiminished. He was the spokesman for the Witan - the governing body of England - when they defied the Danes and elected an English King, Edward, later called Confessor.

His eldest son was Swein, a true black sheep! When he was twenty four he seduced an Abbess. For this unusual sin, he was exiled, but later forgiven. He then murdered his cousin, Beorn. Again, he was exiled and forgiven, but on the condition that he did penance in Jerusalem. Having walked there barefoot, he died in Constantinople on the way home.

Harold was his second son. Much in the stamp of his father, he came through many vicissitudes at his fathers side. He was banished with the rest of the family in 1051, when King Edward's Norman advisors got into a bloody little fight in Dover. But he was back the next year with his father and faced the King across the Thames. The Witan negotiated a peaceful settlement which returned to the Godwin's their lands and power, thus avoiding a civil war.

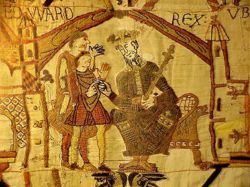

The next year, Godwin died and Harold took over as the most powerful man in the kingdom, second only to the King. During the remainder of Edward's reign, Harold Godwinsson became Dux Anglorum, a title created for him. When Edward died in January 1066, Harold was the choice of the Witan and the people. It is likely he was the King's choice, too, but the deathbed account is in guarded terms as the writer had a Norman audience to please.

"Into Harold's hands I commit my Kingdom."

King Harald Hardrada of Norway

Hardrada was King of Norway. He had a brilliant career as a soldier. He had fought for the King of Novgorod and spent some years in the service of the Empress Zoe in Constantinople. He fell out with her over the division of war booty and came home to Norway in 1042.

The King of Norway at the time was Magnus the Good, but Hardrada was so rich and had such a fearsome reputation, that Magnus gave him half his Kingdom. He came to rule the whole of Norway when Magnus died in 1047. The Danes, who had been ruled by Magnus, refused to accept Hardrada as King. Hardrada was incensed and spent twelve bloody years trying to conquer Denmark, latterly in the hands of Ulf, cousin to Harold Godwinsson. In the end, he failed and signed a pact with King Swein of Denmark in 1063.

He had a large number of warlike followers who were bored by two years of peace. Tostig, the renegade brother of King Harold of England, arrived in Norway to try to gain support from Hardrada. Led into the delusion that the English Earls would support his tenuous claim to the throne, Hardrada gathered a large invasion force and arrived in the area of York in September, 1066. He beat the hastily gathered local army at the Battle of Fulford Gate, took York and retired to his fleet at Riccal.

He had demanded hostages from York and set out to meet them at Stamford Bridge five days later. They were not expecting trouble and a lightly equipped token force accompanied the King. They were surprised by King Harold, arriving with a fully equipped army who brought them to battle there. After a bitter fight, in which both Hardrada and Tostig were killed, the English army had the best of it, although many men were lost on both sides.

A feast was held in York a few days later and it is said that King Harold was actually at meat when the news of William's landing at Pevensey reached him.

The Battle

Within days, Harold was again in London, sending messages across the whole of southern England. The word was that the expected invasion had come at last and that the army was to gather behind the ridge overlooking the Santlache valley "... by the old apple tree." The exact spot is no longer known, but it is likely that the tree grew at the cross roads of the London road and may have stood on the hill where the windmill now stands in the town of Battle in Sussex.

Not long after dawn on October 14th 1066, the Saxon scouts reported to Harold that William was moving north with his whole army. At the time, it was not good cavalry country, the road north from Pevensey was on a ridge of land surrounded by trees and marsh. The speed with which William had moved from his bridgehead at Norman's Bay probably caught Harold by surprise. Only two days had elapsed since his message had gone out and men were still arriving to join his army.

Nonetheless, Harold took the high ground, spreading his men along the ridge overlooking the valley, denying William access to the London road. The story goes that the first blows were struck at about ten in the morning and for many hours the Normans could make no impression on the English.

"All day long they stood there and we could not move them."

In the front rank of the English army were the Huscarls, Harold's personal Hearth Troop. These were the best men of their day, heavily equipped with long mail hauberks, helmets, kite shields and the great broad-axe which had been the trademark of the Huscarls since Cnut's time. They were good at what they did and the axes were much feared.

(The Webmaster would like to add here that the Norman cavalry was probably under orders not to engage the enemy directly, but to hit them at range with thrown javelins. If you read on further, it becomes patently obvious that if the Saxon line got hold of a horseman, then he was doomed to be converted into sausages. The Norman Horse rode up the hill on the left as you look up the site, cut right to offer their shielded side to the Saxon wall and all the missiles that came from there, galloped just out of reach and launched their javelins at the masses. As soon as they had done that, they then retired to re-load at the base of the hill. Just what I would have done.)

"The axes of the Huscarls cut through man and horse alike."

They had a great esprit de corps, and this may have been their undoing. The Normans started to ride along the Saxon line, throwing in javelins. As men fell, so the Huscarls closed their ranks, not allowing the lesser men behind them to come to the front. Within a short time, the ranks of men were so tightly packed together they could not fight effectively.

"They were so tightly massed together that the dead could not fall."

There was much bitter fighting and William had three horses killed under him. At one time, the word went through the Norman lines that Duke William was slain and the heart went from the invaders. But it was not so. Remounting, he took off his helmet and rode up and down the line shouting to his men.

"See, I am not dead and with God's help we shall win this day!"

Then William directed his Breton archers to shoot up into the air, the arrows falling upon the tightly packed English who could not even raise their shields to protect themselves. Neither the technical ability nor the equipment of the archer at war at this time should not be confused with that of the English or Welsh archer four hundred years later at the time of Agincourt. The bows were of lighter draw weight and men seem to have drawn to their chests rather than the chin or ear. Thus, both their accuracy and the speed and power of the delivered missile was inferior.

(The Webmaster would disagree on this point about the 'chest draw'; because very early images 'show' that people had already learnt that drawing to the ear or chin was far more accurate. Also, Neolithic bows found virtually intact, when replicated draw to the chin very well. It is the only sensible way to aim well and achieve some success with the bow. Otherwise it would have died out in favour of much more effective tools. Even today, the bushmen in southern Africa who have very little contact with modern man can be seen today drawing to the chin. It speaks volumes that they still insist on using the bow for all it's advantages in the face of modern weapons. Curiously enough, their 'own' bow is a long bow with all the hallmarks that come with that style of bow. It goes without saying that they didn't learn this from us 700 years ago after Agincourt etc.

What does set 10th century bows apart from the later and more deadly bows of the 1300s, is their lighter draw weight. Still enough to harm and possibly kill a man, but still a hunting tool really, and the real reason that it was only a sideshow weapon in big battles is that the arrows only just penetrated limewood shields. This we've proved since with practical experiments. So if you kept your head down and watched what was going on, you could get away with it.

The bow was good only against the unwary and large masses where you were guaranteed to hit something, and with a bit of luck catch some unfortunate in the eye.)

Even so, the arrow shot was withering at close range and great damage was done to the English. Eventually, a sortie was made against them and the Bretons turned and ran. We shall never know the right of it, but a good number of the English right flank pursued them, were cut off on a small hill and there cut to in the full view of their comrades, who were unable to help them.

This turn of fortune in the early afternoon gave the Normans the opportunity they had been waiting for. Now for the first time they had access to the top of the ridge and fiercely attacked the English flank. Still the English ranks could not be broken and although the fighting continued with little pause, the sun had set before the end came. It is reasonable to assume that the Fyrdsmen, a loose militia of lightly equipped men who had already given their required service to the king that year by manning the coast against the expected invasion throughout the summer, were among the first to fade quietly into the fringes of the great forest of Andraeswold that stood behind them. The men of the Select Fyrd and the Huscarls fought on, broken up into isolated groups by the repeated Norman cavalry attacks.

"When the stars came out, men were still fighting."

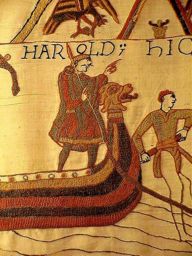

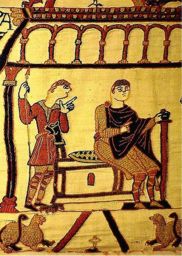

With the relative safety of the line gone, the Huscarls formed a ring around the king. With the king were the standards of England; the Dragon standard of the line of Cerdic, the ancient House of the kings of Wessex; and the fighting man, the personal marker of Harold Godwinsson, worked with silver and gold thread upon in red and white Byzantine silk by Edith, his wife. Fighting a desperate and failing action against repeated Norman attack, the king was beset on all sides. It may well be that the incident pictured on the Bayeux Tapestry of Harold plucking the arrow from his face happened in these closing moments of the battle. Baudri of Bourgueil, writing thirty years after the battle, was the first man to mention an arrow - but not the last ...

"William, in the company of Count Eustace of Boulogne, saw Harold from afar. He was fiercely hewing at the Normans that beset him. William called Eustace to help him and they rode with two other knights to give him battle. William, Eustace, Hugo of Ponthieu and Giffard came to the hill top and burst through the English they found there. They came upon the king and hewed at him with their swords. One stabbed him in the chest, another cut off his head and another slashed at his vitals, spilling them upon the ground. This last man cut off the king's thigh and carried it away, but William was much angered by this vile deed and sent the man from his service."

So the end had come for the last of the Saxon kings, Harold the second of that name, Dei Gratia Rex, Dux Anglorum and Eorl of Wessex, port and shire reeve of this and that, bearer of other less resounding titles. Some said he survived the battle and occasional reports came of him in the generation of native English rebellion and ruthless suppression that followed - but it is, to say the least, unlikely.

The italics in this piece are quotes from the Carmen De Hastingae Proelio ("the Song of the Battle of Hastings"). It is thought to have been written before the end of 1067 by Guy, Bishop of Armiens who was probably an eye-witness of the battle.

In the weeks that followed, William and his army made an complete circuit around London. It is hard for us to understand why, but it may be reasonably assumed that he was unwilling to believe that he had succeeded so well at Hastings, killing almost the entire warrior aristocracy of England that were left after Stamford bridge.

On Christmas day, 1066, he was crowned King of England in Westminster Abbey with great pomp. During the ceremony, there was a commotion outside and his soldiers set fire to a house. It is said that the king's fingers whitened as he gripped the arms of the throne, but no attack came.

Conquered peoples often see little difference after the fact, but William did more than "remove the heads of the flowers", as another conqueror directed his son. He distributed the land of England amongst his men, rewarding directly their service in war. Thus, he brought his domination of the country into the lowest home, the poorest farm and the simplest lives were affected directly by his coming.

William survived for twenty years after the battle that secured for him and his successors the flower of Europe. He was killed in a riding accident, when his saddle's high pommel was driven into his abdomen, rupturing his stomach. He lasted for four days in great pain, and when Confessed, asked for absolution for the lives that had been lost at his hand since the age of eight. At the last, it seems that the subjugation of England bore hard upon his mind. His dying words were recorded thus:

"May God forgive me, for I have taken that which was not mine ..."

His bloated and rank corpse was buried at Caen amidst confusion and his tomb was decorated and desecrated by turns in the following centuries. Now, only a thigh bone lies beneath the simple slab there, inscribed with his name.

No-one knows what became of Harold's body. By tradition, his mangled body was set by William within a cairn of stones on the cliff overlooking the English Channel.

"There," William is recorded to have said "Harold may yet guard the coast of the land he loved so much."

Within a year, Harold's bones were retrieved by monks of the order he had so piously supported all his life and he was laid to rest at Waltham Abbey, behind the alter in the Church he had founded. So the slab there records.

Of his great house at Bosham on the Solent and Edith's house at Nazening near Waltham Abbey nothing is known to remain: like their owners, they have been washed away by the centuries.

Little other than the names and the deeds of the players of this great drama have come down to us across almost a thousand years and it is perhaps fitting that the lives they lived came together finally in what was to be the most important and seminal event in the continuing history of the English people.

1066: the Battle of Hastings.

Much of this article is the work of Mr Robert Gunn. We are very grateful to him for most generously allowing us to use this piece on the Battle of Hastings.

Robert Gunn MA is a professional historian of mediaeval history who studied in Scotland and in the USA. He is a published author.

He used to host more of his work on www.clan.com/history, but this site is now down. Much of his work can now be found at the skyelander website.